A little more than an hour north of Santiago, Chile sits Cartagena. Like an old ship left in the harbor, this coastal town is slowly rotting away — its sidewalks are crumbling, its mostly abandoned houses and buildings are collapsing, and the streetlights rust and flicker. Looking around, one could easily imagine the city sinking to the ocean floor.

As tourists, we typically travel to places we find lively and vibrant, however there is something equally alluring about a city in this state decay.

Here, there are a few tourist attractions, but nothing that would make it into a Lonely Planet travel guide. When TripAdvisor shows “0” hotel recommendations and “0” relevant forums, you know you’ve chosen a peculiar destination.

In Cartagena, popular activities include riding the old horses down the littered shoreline and fishing in the deserted bay. For around a dollar each, you can tour the pirate caves — according to local legend, this cluster of large caves once sheltered a band of pirates and at least one old hermit.

Almost everyone strolls the boardwalk that connects the two beaches, “Playa Chica” and “Playa Grande.” Lined with stacks of empty or abandoned buildings, here visitors can shop the souvenir stands and bring home a Cartagena seashell ashtray or coin pouch.

For lunch, you can dine at one of dozens of traditional Chilean restaurants, hole-in-the-walls called Picas, where you can order a heavy Chilean dish like conger-eel soup or fried seafood empanadas.

If you’d like to stay a few days, most hotels are rundown mom-n-pop establishments but cost only around $8 to $10 a night. They offer “sea-side views” with drafty rooms, musty bedspreads and rickety furnishings. Breakfast is not continental.

Each year, nearly 600,000 tourists, mostly low-income Chilean families and couples, enjoy a modest vacation at Cartagena — typically the only one they can afford.

It’s a far cry from the exotic destinations Chile has to offer, and around Santiago, the word often heard to describe Cartagena is flite — derogatory slang meaning “trashy” or of low socioeconomic status. Ironically, the city was the exact opposite a century ago.

Cartagena’s golden era began in 1890, just after Chile seized the Antofagasta nitrogen fields from Bolivia and Peru in the War of the Pacific. The nitrogen provided a lucrative market abroad, and the Chilean economy boomed. Wealthy Chileans became substantially wealthier and, in imitation of European high society, began summer vacationing. They chose Cartagena for it’s proximity to Santiago.

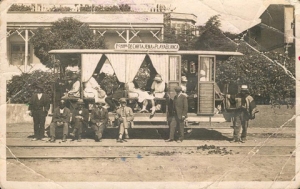

Just 20 years before that, the city was a small fishing village of some 25 families. But within a decade, Cartagena was transformed into Santiago’s first vacation destination. To enjoy the pristine beaches and fresh air, travelers endured a two-day journey via carritos de sangre, horse drawn carriages that ran on a system of rails. Along the mostly barren coast, they assembled all the necessities of an opulent lifestyle — luxury hotels and restaurants, mansions and even castles.

For society’s most influential and affluent, i.e. foreign diplomats, bankers, European merchants and even two former Chilean Presidents, Pedro Aguirre and Ramon Barres, Cartagena was a place for escape and relaxation. Visitors strolled the beaches, attended extravagant dinner parties and enjoyed symphony concerts.

Then in 1930, an official railway delivering passengers from Santiago to Cartagena was constructed. The costs of travel cheapened and Cartagena overflowed with middle and working class vacationers. The privileged sensed the city was in decline and crossed Cartagena off the map. They sold or abandoned their homes, relocating to more exclusive, less accessible destinations.

Afterwards, the city remained a favorite among less extravagant Chileans and was still prosperous a decade later. During the 1940s, Cartagena became known as the “cultural capital” where many of the country’s most recognized artists once lived, including avant-garde poet Vicente Huidobro and painter and writer Adolfo Couve.

Today, the home of Couve, an early 1900s mansion known as The Villa Lucia, is now a museum, El Museo de Artes Decorativas. Tours cost $3, and inside you’ll find the decadent lifestyle typical of affluent Cartagena residents perfectly preserved. The mansion’s original owners hailed from Italy and designed it in the style of an Italian Villa. Like many luxury homes here, practically all construction materials -- including windows, doors, fixtures, flooring, and even furniture -- were imported directly from France, England and Geneva.

Couve resided here for nearly 40 years until his death in 1998. He prefered the city for its relative isolation and unique panorama of Chilean culture. In 1975 he wrote, “This beach town perfectly represents the mixture that in the end we are all made of: the combination of native and European that is plastered into the homes and grand palaces built into the hillsides around Cartagena by the wealthiest families of the early 20th century.”

Many of Couve’s “grand palaces” still stand today, though most are abandoned and in serious disrepair.

The most well known is Forster Castle (above), which sits above the boardwalk and has long served as the subject for dozens of Cartagena postcards. Constructed in 1930 by Sir Guillermo Forster, lawyer, politician and diplomat, this Mediterranean-style castle served as a summer house for him and his family.

Like most things in Cartagena, today Forster Castle is rotting away. Guarded behind iron-gates and barbed-wire fencing as a protected city monument of the patria, the adobe structure is slowly submitting to decay from the wet sea breeze and heavy rains.

So many have come in and out of this city for so many decades, yet few have taken the time to preserve it. Thankfully, today, historians and loyal locals are collaborating with the city to try and restore the many mansions and palaces significant to Cartagena’s history and patria.

One such example is the house of Vicente Huidobro. Though not nearly as well known as national icon Pablo Neruda, Huidobro initiated the avantgard “creacionismo” poetry movement and is considered to be one of Chile’s four greatest poets.

Atop a hill overlooking the city, the poet inhabited this modest early 20th century home until his death in 1948. The house sat abandoned for many years until 2012 when, under the direction of Santiago University, the house was converted into a museum. Seven rooms contain a chronological display of Huidobro’s life and career, including personal affects, letters and valuable antiques.

Just a 10-minute walk up the hill, you’ll find Huidobro’s tomb. When the poet died of a stroke, he was buried as he had requested in his will — on a hill with a view of the Pacific Ocean. Like a classic Huidobro poem, his gravestone reads “open this tomb, at the bottom of this tomb you will find the sea.”

Together these and other attractions add to the prevalent sense of the past that makes Cartagena magical. You can feel it when you walk down the empty streets, and look up into the darkened windows. The city may have gone out of style 72 years ago, but there’s something fascinating about a place now so passé.

Like an old man, this city knows itself well. Having lived a long and fulfilling life, Cartagena has many stories to tell. As a tourist, the adventure is in discovering these stories of what has been. And the mystery is what will become of it.

PREVIOUS ARTICLE

Kiva comes to Oregon! →NEXT ARTICLE

How to create opportunity for women business owners in Iraq →